Provincial Russian Urbanism:

Shaping Catherine the Great’s Imperial Space, 1760–96 and After

By Albert J. Schmidt

(Unpublished Work © 2021 Albert J. Schmidt)

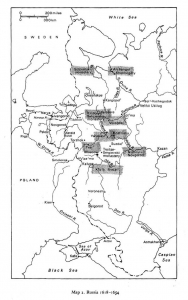

This shaping of an infrastructural colossus achieved its apogee in central or Interior Russia during Catherine’s reign although work had originated with Peter I (1689–1725) and continued into reign of Nicholas I (1825–55).2 Appraised by Shvidkovskii and detailed by Robert E. Jones in his seminal article on urban planning,3 this endeavor, really a classical one, played significantly in Muscovite Russia’s momentous expansion.4 Jones noted the planning of more than 400 towns and cities, an undertaking which “produced a conscious uniformity of urban design throughout the empire.”5 Besides highlighting a milestone in urban history, this shaping of an empire of classical cities epitomized both the imperial vision and taste of Catherine and her successors.

Provincial Russia’s new look stemmed notably from two calamitous events—a fire which destroyed the Volga city of Tver’ in 1763 and the Pugachev peasant uprising in 1773–75—both of which revealed flaws in the management of Catherine’s sprawl. Correcting them included moving her urban planning and building apparatus from St. Petersburg and Moscow to Tver’. After inspecting a restored Tver’ in 1767 Catherine composed the Great Instruction ,which revealed her thoughts about cities. Her provincial urbanism, like Peter the Great’s Petersburg, played well politically by recasting a backward Muscovy with the trappings of a European power.

Further, this paper looks at Catherine’s urbanism through the lens of a built environment—such refurbished central Russian cities as Arkhangel’sk and Vologda in the north and others nearer Moscow such as Iaroslavl’, Tver’/Torzhok, Kostroma, Kaluga, Kolomna, and Tula.6 This is the focus rather than that of founding new ones. Not detailed here but highly germane to this urbanization are other cities in central Russia, settlements in the Russian North,7 in the south on those lands won from the Turks,8 on the lower Volga,9 in the Urals,10 and in distant parts of Siberia11—if only to show the extent of Catherine’s planning and planting an urban empire. This paper even touches on the empress’s skeletal administrative centers, those strategic cogs established by 1775 legislation to facilitate governance. Founded frequently in remote locations, most centers achieved only modest success in evolving as urban centers.12 As such standard bearers they, too, publicized Catherine II’s pursuit of a European look—a neoclassical/geometric one—conveying order as embodied by an expansive imperial Russia.

Catherine’s cities were intended to anchor her empire.13 Like those outlying ancient Rome, Russian cities were rooted in an imperial/legal system linking metropolis to province. Their classical layout–one of architectural Reguliarnost’ detailed here in select exemplar provincial cities mattered to Catherine as it had to her Roman forebears.14 Russian neoclassical urbanism, moreover, piggy-backed on a global building culture the enlightened governance of which, like Rome’s, often bore a stigma—that of autocracy.15

The conclusion examines classical urbanism after Catherine—as championed by Alexander I (1801–25) and Nicholas I and facilitated by the gifted Scottish architect/city planner and imperial strategist William Hastie (aka Geste) and architect Vasilii Petrovich Stasov. The continuity of their model projects with Catherine’s in shaping imperial space is evident in Hastie’s urban blocks and squares and residential design and Stasov’s of commercial entities. Russian urbanism considered in the context of high territoriality is also central both strategically and aesthetically to this narrative.

I. Catherine II and Enlightened Governance16

Eighteenth-century Russia was blessed with two of the ablest monarchs in modern European history, Peter I and Catherine II. Their styles of rule reflected not just differences in personality and sex, but also the sophisticated and Europeanized nature of the Russian elite by Catherine’s time.

Dominic Lieven, The Russian Empire and its Rivals

Catherine was an adventuress of genius; she was never sated by yet another military campaign, another lover, another masterpiece. Her unquenchable thirst for culture was a sort of barbaric instinct whose avidity knew no bounds, her imagination was limitless.

Germain Bazin, The Museum Age, as quoted by Katia Dianina, “Art and Authority,” p. 632.

Unlike her contemporaries Maria Theresa of Austria and Frederick II of Prussia, Catherine II did not possess an administrative infrastructure for governing, really managing her space; consequently, this enlightened empress had to invent her own. She did so especially during 1775–85, although she had taken to top/ bottom despotic planning even earlier. Just as Catherine stocked her Hermitage collection with masterpieces, she projected new towns and cities and restored old ones. In doing so, she established new vehicles for planning and building, engaged in training and supervising her architects, and even concerned herself mastering professional details. Although Russia’s need for rational government inspired Catherine’s provincial urbanism, the back story is her mentalité: the passion she evidenced changing the outlook of her subjects, at the same time satisfying her own autocratic appetite for shaping her cities. The provincial cities examined in this study are emblematic of her personal tastes as well as her pursuit of a new role for Russia in Europe. The Enlightenment was propitious for an activist like Catherine II to seize the moment: her urbanism reflected what mattered to this sovereign in this Age of Reason.17

In the early 1760s the Panin Party within the empress’s court counseled her on rational governance.18 Later, after Catherine’s marrying such rule to expansion cost her Panin support, she tapped the wisdom of French Philosophes—Montesquieu, Voltaire, Diderot, and d’Alembert—and the sculptor Falconet.19 She also found in the Swiss intellectual Friedrich Melchior Grimm a patient listener to whom she once famously exclaimed, “Our storm of construction now rages more than ever before, and it is unlikely that an earthquake could destroy as many buildings as we are erecting.”20 Besides these intellectuals Catherine relied on talented Russian architects like Vasilii Bazhenov and Ivan Starov, both apprentices in 1760’s Paris to the famed classicist Charles de Wailly (1730–98).21

The empress, moreover, proved receptive to the mercantile and administrative ideas of the German Cameralists, whose politics have been characterized as those of a “well-ordered police state.”22 Cameralists and Philosophes alike inspired Catherine’s legislative agenda, especially those reforms dating from 1775. Historian Richard Wortman has reminisced about Catherine’s winning the sobriquet Russian Minerva23 while Alexander Martin labeled her principal accomplishment the imperial social project, contending that it “created the framework for urban governance down to the era of Great Reforms.” He further represented it—perhaps over generously—as Catherine’s attempt to escape the “curse of despotism and poverty” by remaking the social estates into an enlightened third one of “new men…steeped in reason and justice.”24

While Catherine’s interaction with intellectuals from distant places and her immersion in German Cameralism seem the stuff of fiction, it was the fiery destruction of Tver’ on the Volga in 1763 and even more the harrowing rebellion led by the peasant Pugachev in 1773–75 that prodded her to act. Following Tver’s restoration in 1767, Catherine visited that city. Her inspection became an occasion for an extended Volga cruise which took her to the river towns of Uglich, Iaroslavl’, Kostroma, Nizhnii Novgorod, and even Kazan’ farther east.25

While these visitations had their festive moments, Catherine seized the opportunity to assess her imperial space. Doing so, she was mightily impressed, writing as she did to Voltaire from Kazan’:

These words signified at the awe by which this empress perceived the vastness of her space and the diversity of her subjects. Even more, she would reflect on the need to manage it in what Willard Sunderland calls a new age of high territoriality, one based on a state’s territorial sovereignty.26

After returning to Moscow from her cruise, Catherine submitted draft legislation for the Great Instruction (Nakaz) to a Legislative Commission.27 This document spoke to both her urbanism and a European vision of rational governance to replace old Russian parochialism. In it she contemplated a new role not just for reorganized provinces and towns but for a faithful nobility who lived amongst them28. That the Nakaz also included manufactures, trade, education, police, participation by a middling sort of people highlights Catherine’s thinking even before the Pugachev revolt. It was, however, that fearsome episode which sparked her Legislomania—a sequence of statutes which she authored, executed, and, above all, proved her imperial mettle.

II. Metropolis and Province

David R. Browder, (1983)

Imperial & Urban Space & High Territoriality: “The Petrine establishment now explicitly regarded territorial space as 1) a resource to be managed…2) a terrain to be shaped and molded…3) .and as a symbol of national pride…The high-water of this process…roughly coincides with the reign of Catherine the Great….This shift to a higher territorial gear was facilitated by the enshrinement of rationality and esprit geometrique as the golden rules of Russian territorial science….”30 31

Willard Sunderland, “Imperial Space: Territorial Thought” (2007)

This imperial relationship that bound metropolis to outlying province, was as crucial to Catherine’s Russia as it had been in imperial Rome. As Anthony Pagden, the respected authority on empire, observed: “Roman history offered a model….This is most obvious…in allusions to Romanimperial architecture with which the capital cities of Europe …are filled….Above all, the term empire designated an extended polity bound by a body of law.” Towns in this budding entity were not projected hither and yon; rather they were, at least supposedly, positioned rationally.32 Their shape was geometric, their texture one of “space and stone,” a landscape of intersecting thoroughfares, plazas, and masonry edifices.33

Despite the cost of Catherine’s wars and the hugeness of her urban schemes, imperial Russia did possess a means to indulge. Abetted by an affluent serf-holding nobility and a cadre of imported and home grown architects, ever resourceful Catherine benefitted as well from an economy rooted in a bountiful production of grain for export, a treasure trove of metallic wealth, and a nascent urban economy.34 Her mobilizing these assets led to a boom in serfdom which underlay the rash of her nobles’ estate building and even her own urban expansion.

Made over interior cities like those mentioned above and detailed below—from Kaluga to northern ones like Arkhangel’sk and Vologda—constituted at once a strategic core of Catherine’s empire and like others formed tentacles of her autocracy as well as a showcase for her urban achievement.35 Although administrative centers traceable to the 1775 Gubernii Statute were of limited scope, they, too, had a crucial role to play in shaping Catherine’s Russia. Called by Jones “the most extensive redistribution of administrative units ever undertaken by the tsarist regime, this legislation embodied “the redrawing of most administrative boundaries and dividing the historic Gubernii into lesser and more manageable ones which, she subdivided into districts (uezdy) and towns.”36 While projected principally for strategic purposes, some cities also improved the Catherinian landscape as well as governance. At least historian Lukomskii thought so, citing building and other improvements by newly installed governors-general like M. Krechetnikov in Tula and Kaluga; Jacob Sievers in Tver; and A. P. Mel’gunov in Iaroslavl’, Kostroma, and Vologda, to name a few (See Lukomskii, Provintsiii, p. 139.)

In decentralizing of her rule (without losing control), Catherine, as noted, relied on the nobility both to manage her imperial turf and as military servitors to combat the Ottomans. As Sunderland put it: “The intensification of [the] new territoriality of the late eighteenth century is particularly visible in the pronounced territorial preoccupations of the Catherinian elite.”37 Charters to the Nobility and Of the Cities, which followed a decade after the Gubernii Statute, further refined Catherine’s governance: in elevating her nobility to center stage, she affirmed her authority beyond St. Petersburg.38

Priscilla Roosevelt has noted how noble properties accentuated perceptions of this decentralization: “Estate architecture…encapsulated an owner’s desire to establish an identity to two opposite directions, upwards by reaffirming links to the autocrat sovereign; and downward by creating an estate reflecting a hierarchical dominance over a local serf society.” Beyond this partnership, there was status. Roosevelt discerned classical architecture’s ties with status as evidenced by lesser landowners’ mimicking the colonnaded mansions of their betters.39

One must ask why did it happen that an affluent nobility became Catherine’s crucial partner in reshaping both her urban and rural landscapes? A plausible but by no means universally accepted answer was again Robert Jones’: contemplating the horror of yet another Pugachev rising spurred Catherine to accept it. Jones went even further, maintaining that Catherine favored a loyal nobility over an incompetent bureaucracy the miscues of which had even fueled the Pugachev episode.40

This reversal of Peter III’s policy of emancipating the nobility from state service (Manifesto on the Liberty of the Nobility, 1762) was linked to a change in land tenure: the pomest’e, by which the nobility had once held land in exchange for state service, now certified their outright ownership of estate land. The consequence was a tighter control (e.g., serfdom) over the peasants who planted their fields and orchards, mined their minerals, and on occasion, not incidentally, designed and built their mansions.

Russian provincial towns which evolved from the late eighteenth century never resembled their counterparts in Western Europe.41 Indeed, economic historian Boris Mironov contended that there was little to differentiate Russian rural from urban space down to 1785, when Catherine’s Charter to the Cities required each town’s adhering to a plan.42 He attributed much of the change late in the eighteenth-century to a rise in prices, not dissimilar to that which had impacted Western Europe two centuries earlier.43 This inflation was especially consequential for the nobility and to Catherine’s politics. In this quasi-Europeanized Russia: the nobility became a privileged elite benefitting as they did from an enhanced serfdom. Their lifestyle became one of voracious consumption—travel, obsessive building—and indebtedness Truly, the nobility’s return to service proved transforming—reversing the autocracy’s time-worn policy of provincial neglect. Where legislation was key, Catherine used especially a middling nobility to manage her space. Cities and administrative centers extended her political reach, providing military and administrative footings for defense, tax collecting, surveying, dispensing justice, and advancing the public welfare.

Catherine paid a price for Russia’s becoming imperial: one of reconciling long-term territoriality with the immediacy of solving local problems. Historian Janet Hartley articulated this problem, by asking: “To what extent did the eighteenth-century autocracy allow or encourage genuine devolution of power to the provinces? Historian Sunderland rightly concluded that “new ideas and practices of territory influenced both the nature, the aspirations of state power, and the national/imperial belonging of state elites from late Muscovy to the age of Catherine the Great.”44

Expansion proved double-edged for Catherine’s urbanism: decentralization did not lessen; rather it fed the “well-ordered police state.”45 Russian cities/administrative centers followed Roman practice of maintaining a bureaucracy intended to dazzle subjects: the planning and building in the provinces conveyed a message of order, power, and secularism, embodying the autocracy as identified by Browder and what Charles Tilly called “the long, strong arm of empire.”46

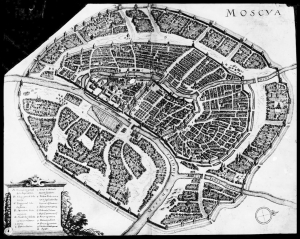

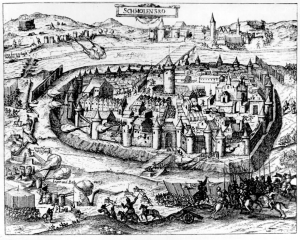

The Seventeenth Century Landscape

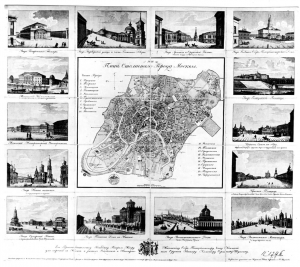

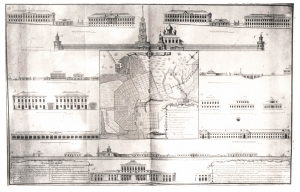

Map of Moscow, 1643 (SMA).

III. Reguliarnost & Gradostroil’stvo: An Anatomy of Classical Urbanism47

Spiro Kostof. (1936-81), The City Shaped

Urbanism’s Vehicle: “The Commission on Masonry Construction for St. Petersburg & Moscow” was crucial during this period of urban planning, 1760-1790.

F. Savarenskaia, O. Shvidkovskii, & F. A. Petrov. Istoriia gradostroitel’nogo iskusstva (History of Town Planning Art) Moscow, 1989).

If, Your Majesty, you could wave your magic wand and build as many houses as you liked instead of palaces, I should still repeat my appeal to you: ‘Build streets.’ And this indeed was done, in all provincial and district towns in Russia, with great energy and determination.49

Diderot to Catherine II as quoted by Shvidkovskii.

Catherine’s success in reshaping Russia’s imperial space, notably the urban, was measured by practicality and taste no less than politics. Historian Shvidkovskii had it right when he emphasized that imperial control over architectural details was such that “only the power of the monarch could accomplish such immediate transformation through construction.”50 Catherine’s authority in determining the look of new edifices and the shapes of her towns was formalized in newly minted town plans, as described by Kostof; the only limit on such authority was the Russian expanse.

So it was that urban shaping proceeded at an unparalleled pace from early Peter I to Catherine’s death (1796), or more accurately, to Alexander I and Nicholas I. Although architects transformed tormented building assemblages—hovels, crowded commercial stalls, and littered courtyards on crooked streets into a verticality of columns—the non-financial costs were also dear. As Daniel R. Browder observed: “Alongside the monumental public buildings the inhabitants took on the proportions of dwarfs”51 Then. too, the architecture of classicism found unqualified acceptance in Russian towns, especially when model designs by decree trumped topography.52

The unwavering line, heralded by the French classicist Pierre Lavedan (1885–1982) as “the very expression of human reason and will,” was crucial in the organization of classical space, whether that of St. Petersburg or Russia’s provincial cities. This exacting line found expression in street configuration, especially axial dominance, and in the linear effect of uniform frontal facades adhering to the “red line” of the street and unbroken horizontal roof lines.53

Lavedan offered a second dictum, a spatial one—whether private or public; square, oval, circular, rectangular, or that reserved for straightening and paving streets. The town center received special consideration, as planners matched architectural look with function. This plaza as public space organized for a monumental perspective was also figured in the politics of the classical landscape: centrally positioned palaces, essential for such an ensemble conveyed a message of power and majesty. In provincial Russia the governor’s residence and especially the edifices of the military occupied commanding sites. Structures accommodating the bureaucracy—the military, judiciary, finance, and police—were also among the few faces of the faraway autocracy which provincials encountered, and then only in select urban centers. When provincial officialdom—ensconced in elegant edifices—issued imperial edicts, subjects were expected to be awed as well as compliant. Newly minted town plans spoke to this matter as well.

An elite nobility was a principal beneficiary, especially, of spacious town centers. Residences there were enhanced by a classical/masonry backdrop—one brightly painted and with an infrastructure of paved thoroughfares leading into the plazas. In sculpting this central void, architects of classicism also planned and planted edifices germane to public health, education, and charities.54 For the privileged few renovated provincial towns brought a new scale of living and social climbing. Public space, the street, long the venue of the people, acquired exclusivity as a preserve for promenading aristocrats and uniformed officers with their ladies.55 Notwithstanding a prevailing provincial boorishness, building surged and its refinement glossed aristocratic provincial society.56

Where cleanliness and hygiene were a concern: factories, coachmen’s stables, tanneries, slaughterhouses, cemeteries, and the like, were shunted to outlying areas. Moving factories—even those in a classic mode—downstream, laying water pipes, and digging drainage trenches accommodated both sanitation and appearances. The cost of this infrastructure, particularly that of the first zone, was presumed the state’s responsibility.57 In treating towns as regal enclaves, the autocracy not infrequently trampled on property rights in pursuit of this royal aesthetic.58

How does one square this narrative of a late eighteenth-century provincial Russia punctuated by urban renewal with a rural Russia of estates belonging to a nobility and in the throes of serfdom? Arguably, this is a portrait of the Moscow region and beyond in the latter years of the reign of Catherine. Historian Paul Dukes suggests dividing this entity into a half dozen clusters, citing: 1) the lower and middle landlord estates, which lay to the south of Moscow along the old Crimean Tatar defense line near Kaluga, Tula, Riazan, and sizable portions of Orel; 2) estates northwest of Moscow around Smolensk, Pskov, and St. Petersburg, once a barrier against Poles and Swedes; 3) lands formerly belonging to tsar and boiars, including Iaroslavl’ and Kostroma north of Moscow; 4) estate lands nearer to and including Moscow with scattered estates of wealthy nobility and churchmen in the north; 5) lands around Voronezh, Penza, Simbirsk and Saratov, which became estate property of nobility; properties of state and church peasants around Novgorod, Vologda, Kazan’, and Perm as early as Ivan IV in the sixteenth century; and 6) a few estates in the far north near Arkhangel’sk, Viatka, and Siberia.59 These lands were in transition: quasi-rural becoming urban.

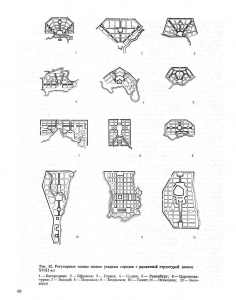

Catherine’s planners divided towns into workable units, rings, accessible to building materials.60 Hypothetically, new construction utilized the brick and stone of old structures in the center, when the first ring was occupied by, say, a kremlin. Less pretentious masonry housing with continuous facades in the same ring faced restrictions in frontal design, height, width, and paint color. As Shvidkovskii has noted, even private houses were subject to official approval and police enforcement.61 A second ring was reserved for small houses and shops, built of wood but usually on stone foundations. Building materials notwithstanding, row houses with continuous facades were fire hazards. Those in a third band, the largest, were wholly of wood; even when flush with the street they rarely possessed a continuous facade.

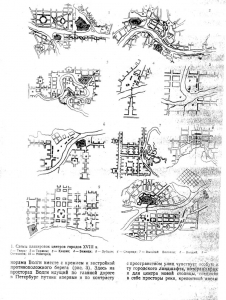

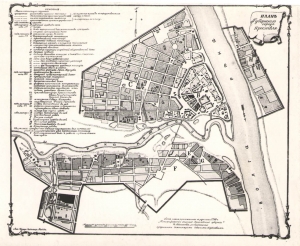

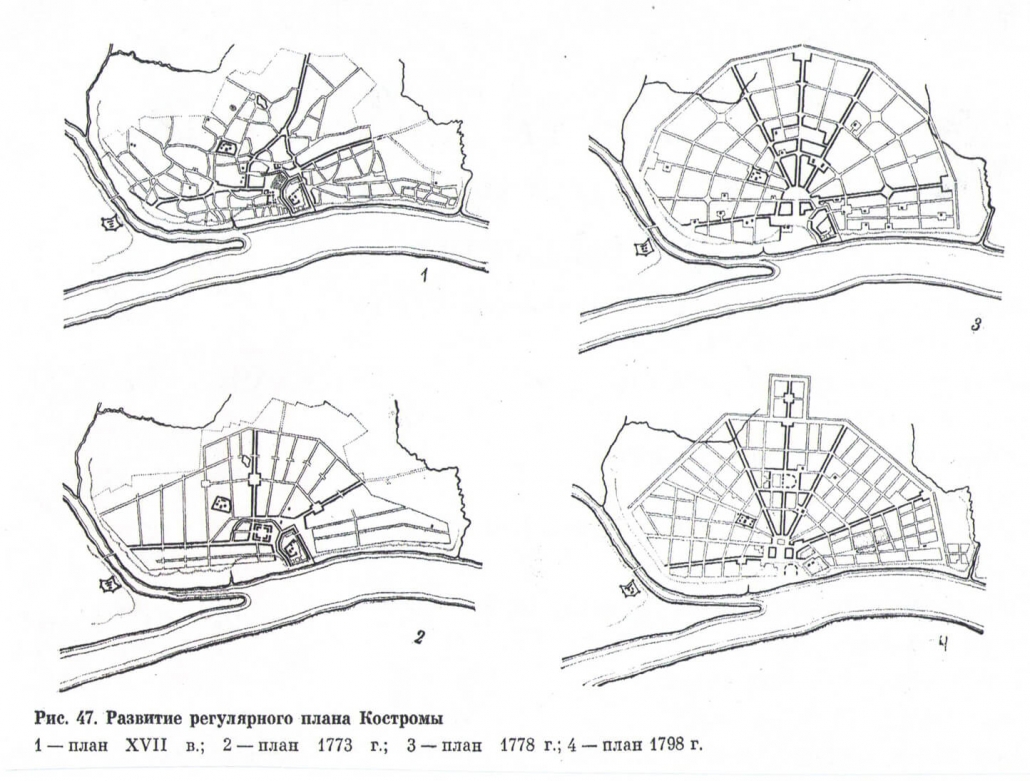

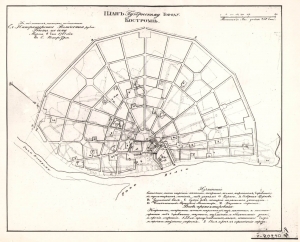

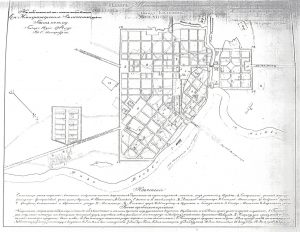

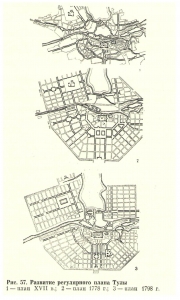

`Russia’s classical cities, like those in the Grand Baroque Manner of a European one a century earlier, assumed diverse shapes—radiocentric and fan-shaped being the two most frequent with rectangular and diagonal patterns incorporated within these.62 The first, which as noted, frequently evolved from a kremlin of protective walls, was translated into a hub with concentric boulevards pierced by radial thoroughfares. Such a radiocentric pattern dominated Moscow’s center while Kostroma’s took on near perfect fan shape. In this aura of abundant public space and linear articulation Russian planners inserted bridges, embankments, and gridiron blocks, straightened riverbeds, and paved canals.

A geometric reordering linked Russian towns not only with the Petrine baroque of St. Petersburg but also with the building styles and layouts of Antiquity and Renaissance Europe.63 Historians as diverse as Igor Grabar’ and Dmitrii Shvidkovskii favored French antecedents, while classicist Georgii Lukomskii tilted toward those of Renaissance Italy. Shvidkovskii equivocated on Russia’s architectural debt to France, crediting military engineers as well as Bazhenov’s classical Kremlin, which had once seemed destined to redefine Moscow.64 There were diverse styles and favorite architects in Catherine’s repertory: by the 1770s her tastes had evolved from a liking of German rococo to a preference for Palladian classicism “that combined the purity of French classicism with a sensual appreciation for…Roman forms.”65 Infatuation with the artistry of Charles Cameron prompted Catherine’s reshaping palatial Tsarskoe Selo, an undertaking intended to link her classicism to that of William Hastie’s, and the making of an exquisite village named Sofiya.66

While it strains credulity to speak of an urban renaissance in late eighteenth-century Russia, numerous towns in the Interior did assume a regular look under the initiative of such Catherinian governors as Krecheshnikov in Tula and Kaluga, Jacob Sievers in Tver, Mel’gunov in Iaroslavl’ Kostroma, and Vologda, and Vorontsov in Vladimir. Their geometric planning and building became synonymous with modernism. Robert Jones held that Catherinian design, which “established the appearance and the character of the modern Russian city,” represented one of the great legacies of this period.67 That Catherine, as noted above, “envisaged the towns as centers of health care, education, and public welfare” also signified classicism’s modern edge.68 Despite its disconnect with Old Russian culture, classicism did win acceptance from diverse constituencies, becoming the badge of such proud elites as the monarchy, nobility, and even a coterie of wealthy urbanites.69 This was especially true of Empire classicism, fueled by the martial glory of 1812–15.70

This new urban look did not just happen. Between the reigns of Peter I and Catherine II—especially with St. Petersburg and Tver’ as models—a mix of talented architects and a well-organized building apparatus spawned an era of rococo/classical building. Besides the construction which coalesced in St. Petersburg and Moscow also impacted their suburbs. As Wortman observed, architects built edifices “that gave Russia its own imitations of Roman architecture.” Such emulation “transposed the political spirit of Rome to St. Petersburg and its environs.” Then, too, foreign architects like Charles Cameron were pivotal in bringing the art of Palladio (1508–80), to Russia.71

By the early 1740s students were learning architectural drawing in the Moscow workshops of Ivan Korobov (1700–47) and Ivan Michurin (1703?–63), both of whom had studied architecture abroad.72 Creeping professionalism became evident by mid-century in a Moscow school founded by the baroque/rococo master Dmitrii Ukhtomskii (1719–74).73 This institute nurtured, among others, the talented Vasilii Bazhenov (1737–99), Petr Nikitin (1735–90s), and the most durable of them all, Matvei Fedorovich.Kazakov (1738–1812). Included also was the transitional (baroque/classical) architect Ivan E. Starov. Planner in Iaroslavl’, Voronezh, and of towns in New Russia, he had studied in Paris, as noted, with the classicist Charles de Wailly.74

The best known of late Catherinian architects were those of the Kremlin School. Founded in 1768 and connected with Bazhenov’s Kremlin makeover, it was involved transforming Old Moscow into a classical one. The faculty included Bazhenov, who had studied abroad as well as under Ukhtomskii, and was himself mentor to Kazakov. Eventually, the latter, tutored, too, by Nikitin, took over the headship of the Kremlin School. As one contemporary observed: the school founded by “the most famous and able architect Kazakov…filled not only Moscow but also all Russia with good architects.” Elizvoi Semenovich Nazarov (1747–1822) and Ivan Vasil’evich Egotov (1756–1814) were early graduates who left their mark on provincial urbanism.75

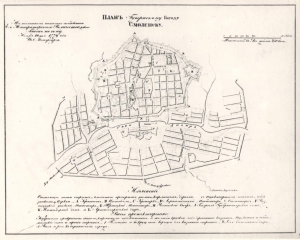

Catherine’s earliest undertaking to centralize urban planning had been the appointment in 1762 of a Commission for the Building of St. Petersburg and Moscow. This central planning agency—which included generals, dignitaries, and corps of architects, surveyors, clerks and initially under architect Aleksei Kvasov—served Catherine in matters of urban building for the remainder of her reign.76 That urban police stringently enforced Commission plans signified the importance the empress attached to these “guardians of [both] the physical and moral order in the towns.”77 Similarly, a new Masonry Bureau (Kamennyi Prikaz),dating from the 1760s, became a vehicle for upgrading Moscow in accord with that city’s 1775 plan.78

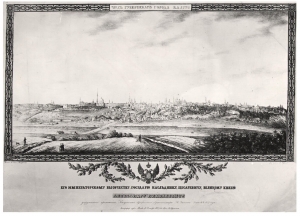

Catherine’s urbanism went beyond the aesthetics of architecture and the artistry of model design albums; it demanded precision in the drafts of city plans, maps, and blueprints; those urban monuments which filled spatial voids and inspired patriotism; the works of talented artists who advertised the new urbanism through cityscapes and views and pictures of edifices and monuments which often provided marginalia for maps and city plans. Kazakov’s watercolor of Tver’ was special in documenting the city’s restoration in 1763.79 Urban scenes like those by the painter Fedor Iakovlevich Alekseev (1753–1824), also won an audience for urbanism, and even nascent nationalism.80 Such sentiments were especially evident in painting the of centennial unveiling of Poltava’s Glory monument.81

Classical urbanism benefitted from the improved draftsmanship of the new cartography and town planning. Historian James Cracraft, moreover, has cited the newly-established Academy of Fine Arts for its offerings in drawing and drafting which spurred architecture, etching, engraving, lithography, and painting as “the chief agency perpetuating [a] Petrine visual revolution”82 and figured institutionalizing the Grand Manner style. S. Frederick Starr perceptibly noted that the Academy’s direct control

The increased output of meticulous maps and town plans accurately and eloquently extolled the virtues of empire, especially in marginalia of mythological, military, and architectural representations.84 As Steven Seegel framed it: “Catherine used maps as expressions of enlightened governance….[Her] maps of…borderland frontiers functioned as a kind of master blueprint for empire.”85 Early in the nineteenth century, especially, albums of model projects and blueprints for city blocks and plazas became preferred media for publicizing a Europeanized Russia in the making.86

Model projects proved critical in planting classical cities/towns in remote places where professional architects were lacking but where their expertise in design if only in albums was required for residential and public buildings, or even stark factories. While such models had been utilized during Peter I’s and Catherine II’s reigns, their apogee occurred under Alexander I when many newly minted plans were approved and issued promptly by one in authority, not infrequently one William Hastie. This master strategist, whose crucial role is detailed below, authored architectural model projects as well as authorize numerous city plans.

Through this new authority and imagery light was shed on both the near provinces and the hinterlands of the North Dvina, the northern and southern reaches of the Volga, the Urals, and even the distant Altai.87 Geographic images, descriptions, and maps gave this Russian expanse a face hitherto unfamiliar to Russians living in and near the two capitals as well as in Western Europe.88 That Academy stalwarts, the St. Petersburg masters Adrian Zakharov and Karl I. Rossi, took Altai and Siberian students under their tutelage is indicative of both the search for talent as well as imperial reach.89 Nearer at hand, cities like Odessa and Kiev cast a further classical glow, emblematic of their new urbanism’s descent from a rich architectural past.

While Catherine’s main purpose in establishing administrative centers in 1775 had been one of governance, people did matter.90 Alexander Martin’s thesis of: Catherine’s imperial social project—that is, one of transforming backward peasants into industrious and virtuous Europeans—is intriguing and even compatible with Martin’s notion of an emergent bureaucratic “middling sort.” Did Catherine ponder possible collaborators with her nobility?91 While the lives of such late-eighteenth-century personages are elusive, David Ransel’s and Alexander Martin’s biographies suggest Catherine as a sometime urban reformer92 to which even Robert Jones subscribed:

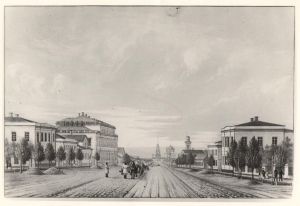

The 18th Century Scene

IV. Catherinian Russia’s Built Environment, per Baron August von Haxthausen, 1840s

August von Haxthausen, as quoted in William Blackwell, The Beginnings of Russian Industrialization 1800–1860, p. 99.

Haxthausen’s 1840’s portrait of a provincial landscape, e.g., “Catherine’s town” is telling: despite Catherine II’s urbanism the traditional village continued its coexistence with newly built urban space. Citing Haxthausen also introduces the ambiguities of Russia’s urban demography, a composite of the scholarship of Robert E. Jones, Arcadius Kahan, Boris Mironov, William L. Blackwell, Thomas Stanley Fedor, Adna Ferrin Weber, Gilbert Rozman, and the incomparable V. M. Kubuzan, each of whom spoke to this crucial aspect of imperial Russia’s budding urban scene.

Jones linked this demography with planning as evidenced in his treatment of the Commission on the Building of St. Petersburg and Moscow;95 Mironov won plaudits for his study of the eighteenth century price rise in Russia; Arcadius Kahan, meanwhile, placed his work on a firm scholarly footing by linking demography to economics in his study of Russian towns, some of which are detailed in this paper. Kahan’s citing Kubuzan as the leading [late nineteenth] specialist on Russian historical population studies gave credence to his own work.

In his demographic treatment of central Russian cities Kahan noted that “more than 8 percent of the population lived in cities during the 1780s.”96 Further, he concluded Moscow’s and St. Petersburg’s population at more than 100,000 each with a combined population of perhaps 400,000.97 Although finding no cities numbering 50,000–100,000, he did include Tula, Kaluga, and Iaroslavl’ among the three with an estimated population between 30,000 and 50,000. He placed Tver’, Arkhangel’sk, and Kostroma in the 10,000 to 20,000 range. Of the towns examined below, only Vologda and Kolomna had fewer than 10,000 inhabitants: by the eighteenth century Vologda’s role in commerce had diminished, while Kolomna’s had never been notable.98 Blackwell, using the dates 1811 and 1840, numbered Iaroslavl’ (23,800 and 34,900), Tula (52,100 and 51,700), and Kaluga (23,100 and 35,000).99 Kahan placed Tver’, Arkhangel’sk and Kostroma in the 10,000 to 20,000 population range. Thomas Stanley Fedor also examined nineteenth-century Russia’s urban population while Rozman, like Kahan, drew on the legendary Kubuzan.

How and when did Catherine’s new or renovated urban centers assume final shape? To judge from Catherine’s disdain for old Moscow she certainly expected her cities to adhere in good time to reason and order, features that fixated all enlightened monarchs. Had not Peter I years earlier banished wooden sprawl on Moscow’s Iauza River by replacing it with a classical Lefortov district? Then, too, Catherine and then Alexander, had forged a classical Petersburg and even contemplated doing the same with Moscow. Provincial urbanization, once begun, seemed never ending, certainly proving to be a task exceeding the making of even a classical Petersburg or Moscow. Historians have proved extraordinarily innovative in narrating it.

VI. Catherine’s Built Environment: Making Nine Classical Cities

Russia’s provincial cities, especially those founded as administrative centers, have on occasion been labeled “artificial” or unrealized. Arkhangel’sk and Vologda were neither. In the north, where the White Sea was key to the Russian economy, the former was founded a century and a half before St. Petersburg. This alternative to Western European markets dated from 1553 when an English vessel arriving in the North Dvina inaugurated White Sea traffic. By 1585 the city of Arkhangel’sk, newly founded on the site of a monastery, had replaced Kholmogory as the principal regional port. In less than a century—the Dutch, having superseded the English in the Russian trade—it became a major entrepot for north European traffic.100

Although sables were largely extinct in the Russian North even by the seventeenth century, they were brought to Arkhangel’sk from Siberia. Salt and copper, exploited especially by the Dutch, were also preeminent in the northern commerce. The port, moreover, was important for the grain market, principally for transshipping Volga rye to Europe. Vologda and Tver’ merchants and even those from Kaluga, Tula, and Kolomna used it as their port from the early eighteenth century.101

The White Sea route was highly problematic: passage between the Atlantic seaboard and Arkhangel’sk was exhausting and dangerous, moreover, the harbor’s shallow waters necessitated unloading incoming cargo onto smaller craft and storing in the Moscow Merchant’s House (gostinyi dvor) before shipment to Moscow. This wooden structure, which combined merchants’ quarters and a warehouse, was probably the largest of its kind. Consisting of 170 rooms and about as many stalls, it was the preserve of the Moscow merchants. Foreign peddlers were forbidden advancing beyond it.102 Following its destruction by fire in 1667, its successors were built of stone.

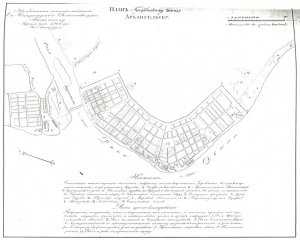

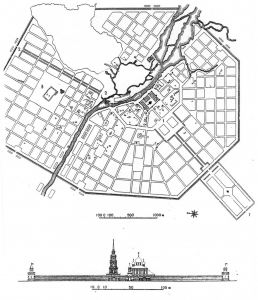

Perched at the tip of a peninsula jutting into the North Dvina, Arkhangel’sk even today evidences the contours of a classical city. The fan-shaped streets emanate from an interior hub toward the river. The city’s axial and central Voskresenia thoroughfare, which originates well beyond the regulated peninsula, fans from the second plaza in its path. It and the other radial streets intersect with the long North Dvina Embankment rather than converge as in Kostroma. The Arkhangel’sk plan was slightly irregular, its city blocks being imperfect squares; at the north end, the angularity of the plazas accommodating the shoreline of the Kuznechikha River. The plans of both 1784 and 1794 show a geometric street grids which continued into the city’s Solombala quarter across the river. Positioned at the intersection of the radial thoroughfares with the North Dvina were imposing edifices, among them the cathedral and the gleaming 1797 gostinyi dvor. Standardized middling (meshchanskie) dwellings also were a determinant in the city’s look.103

Yet it is a mistake to exaggerate classical Arkhangel’sk masonry cast: at the end of the nineteenth century, it was still, par excellence, the wooden city. An “Arkhangel’sk house,” according to a nostalgic writer, was one “largely standard in design and construction, but endlessly variable and individual in detail and richly decorated in a national style.”104

Arkhangel’sk’s commerce stimulated the economies of other northern towns—Velikii Ustiug, Tot’ma, and, especially, Vologda and Iaroslavl’.105 Goods brought into Arkhangel’sk from Europe and destined for Moscow was moved south on the North Dvina to the Sukhona and then on to Vologda on the Vologda River, until winter when these rivers froze. Long a way station for goods shipped from the north, even before the founding of Arkhangel’sk, the city was pivotal vis-a-vis Iaroslavl’, the principal distribution center for incoming European goods.106 Vologda, like Arkhangel’sk, had its merchant’s frame warehouse, which included storage rooms, a hotel, and a church.

* * * *

The merchant trek from Vologda along the Moscow road was routinely delayed until winter when hard-packed snow made travel by sled easier. Merchants either passed through Iaroslavl’ en route to Pereiaslavl’ Zalesskii, Rostov, and Moscow, or they simply lingered in Iaroslavl’ from which they shipped their wares to other Volga towns. Like Arkhangel’sk, seventeenth-century Vologda engaged in the salt trade, which originated in Solovetskii Monastery, along White Sea shores at Tot’ma, and nearby Spaso-Prilutskii Monastery. The city also prospered during these years from commerce in copper.

Vologda enjoyed political prominence in the sixteenth century when it served as both an administrative center and a refuge for an embattled Ivan IV. For a time, he may even have contemplated making the city his capital. That Catherine II designated Vologda, Arkhangel’sk, and Velikii Ustiug provinces vicegerencies (namestnichestvy), principally to maintain order in the Russian north, no doubt motivated her sprucing it up.

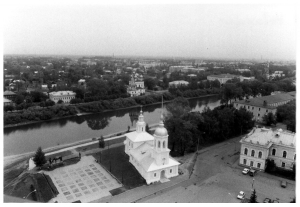

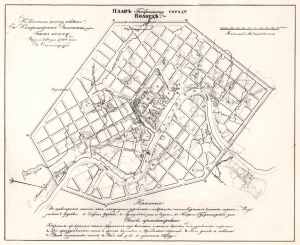

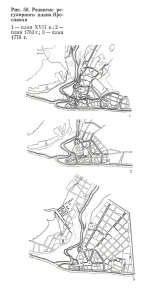

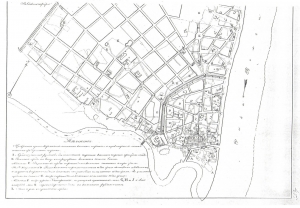

Vologda’s inviting site consisted of 1) the City (Gorod)—the kremlin, Sofia Cathedral, and the famed Archbishop’s Courtyard—located at the Vologda River’s confluence with the Zolotukha; 2) the Lower Settlement (Nizhnii Posad), adjacent to the Archbishop’s Courtyard; 3) the settlement beyond the river (Zarech’e); and 4) the Upper Settlement (Verkhnii Posad). The replanning of Vologda at the end of the eighteenth century resulted largely from the changes in the first two site elements; however, building merchant villas in Zarech’e along the river and alterations of the Upper Posad played significantly in making Vologda classical.

Although Vologda did not acquire so pronounced a /geometric look as did Tver’, Kostroma, or Kaluga, a renovative plan had actually begun earlier. Confirmed as a namestnichestvo with a governor in 1780, the essential configuration of the city had been evident as early as 1700. At that time many of its numerous wooden structures, especially churches, were razed and replaced by masonry ones. The Archbishop’s Courtyard, the center of the seventeenth-century city, remained into the next. For Vologda, as with other towns, natural disasters—a fire in 1773 and flood in 1779—effected its classical conversion.

The geodesic survey made after the fire of 1773 showed the Lower Posad reaching beyond the Little Blagoveshchenskaia to those cross streets which in recent times constituted the Oktiabrskaia/Hertzen Ring. As Lower Posad’s street grid veered toward the river, the Piatnitskaia (sometimes Mal’tsev Street), became the central axis converging on the Sofia Cathedral in the Archbishop’s Courtyard. The city limits in Zarech’e stretched only to Kalashnaia, or modern Gogol Street.

The architects of a new Vologda likely pondered street configuration long and hard, for the Piatnitskaia had no place to go. Although its termination in the vicinity of the Archbishop’s Courtyard was feasible, the space (which became Gostinodvorskaia Plaza and more recently Pobeda, or Victory Prospekt) at the convergence of Piatnitskaia with the lower Great Blagoveshchenskaia (more recently Batiushkov) was too small to be monumental. What to do?

A group of architects led by Petr Trofimovich Bortnikov devised a novel solution. They joined the Archbishop’s Courtyard, which, after all, was the city’s earliest central plaza, to a new administrative center. They did so by shifting the Great Blagoveshchenskaia/Kirillovskaia (later Mirskaia) axis roughly forty-five degrees toward the Zolotukha River, where endless space allowed for a cavernous square. This diversion of an axis, which had originally pointed toward the Courtyard, resulted in its resting nearly perpendicular to the old grid. In the newly configured Nizhnii Posad the axial streets converged on a monument far less auspicious than the ancient archepiscopal complex: it was simply a single-arched, four-towered stone bridge, which spanned the Zolotukha River. However nondescript initially, this sector of the river front was soon inundated by commerce and made fashionable by promenading gentility. At the confluence of the Zolotukha and Vologda Rivers a spacious administrative plaza took shape. Rectangular with symmetrical half circles on each end and pierced by pairs of diagonal and perpendicular streets, they presented striking contrasts, as evident in the 1784 plan, to the old city center altered just a few years earlier.107

The fire of 1773 and the flood six years later spurred both planning and masonry building. The changes wrought during these years by architects A(lexander?) Bortnikov, Sokolov, and perhaps the most important among them, Levengagen, effectively elevated this ancient city to a resplendent classical one. Although dating classical architecture in Vologda is imprecise, the most important official structures—the governor-general’s mansion and administrative, commercial, and public buildings—were erected in the 1780s and early 1790s. The same was true of masonry residences, the most impressive of which were built along the embankment. A rococo lag, however, punctuated by their flat facades, ornament, cornices, voluted pilasters, and countless windows prevailed among them.

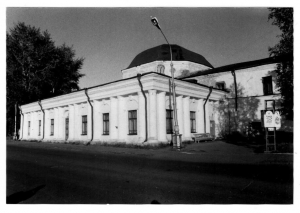

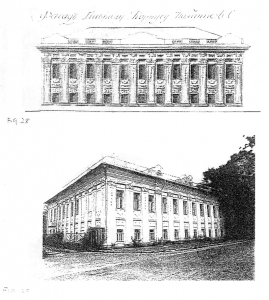

The governor general’s mansion was one of the first masonry edifices (1780–83) after the designation of Vologda a namestnichestvo. Built according to Levengagen’s design, it was massive, L-shaped, and also reflecting the rococo lag characteristic of provincial architecture of this period. Absent the portico and pediment which high classicism demanded, the building instead featured cylindrical corners and myriad windows, twenty-four of which reached across the facade.108

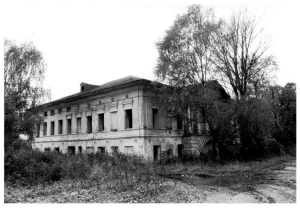

The Zarech’e Embankment with its late eighteenth century chic homes typified the new Vologda. A few of these masonry mansions, like the merchant’s dwelling on the Sreteiskaia (later Third Red Army, or Krasnoarmeiskaia) Embankment survive.109 To this day it remains a handsome and substantial two-story block the facade of which is interspersed with ornate pilasters, cornices, and windows capped with lintels. Another late rococo survivor, no. 25 on the embankment, dates from 1777. Also replete with luxuriant windows, cornice, and pilasters, it has an eye-catching facade the lower portion of which is rusticated.110 Admiral I. Ya. Barsh’s estate at no. 11 was the most stately on the quay. Its facade brandished a dozen pilasters and eleven windows on each of its two stories as well as a flashy cornice and equally dazzling wall ornament in relief.111 Nearby (on what later became Red Navy, or 16 Krasnoflotskaia Embankment) Maslennikov House was of a plainer sort but recognizably rococo from its array of pilasters, cornice, and windows.112 The sugar refiner Vitushechnikov and the merchant Varakin also built riverside homes, at once imposing yet unpretentious compared to earlier rococo and later classical ones.113

One exception to this late rococo bloom, at least regarding its river facade, was the Skuliabinskaia Almshouse. This early 1780s edifice, devoid of ornament, bore a powerful six-columned portico with pediment and rested on an elevated foundation. Like the massive Indigents’ Hospital, it was reworked in the classical style of the next century. Its two-story facade of twenty-one windows across shouldered a six-columned portico with pediment; a wing at one corner was capped with a cupola.114 These new embankment edifices and the street configurations gave a classical glow to this ancient city.

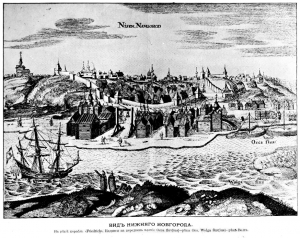

Next to the White Sea the Volga River basin was Russia’s central avenue of commerce during the seventeenth century. It drew trade from Arkhangel’sk in the north and Astrakhan in the south, where Persian ships unloaded their silk.115 This southern commerce, moreover, greatly enhanced down-stream settlement. The Volga trade, however, had a huge drawback: although ships moved easily with the current, they had to be rowed upstream. The first two stops from the south were Kazan’ and Nizhnii Novgorod, from which merchants often transshipped their goods, either by way of the Oka or overland. Cities like Iaroslavl’, Kostroma, Tver’, Nizhnii Novgorod, and Kazan’—disheveled, unsanitary, and fire prone—not surprisingly were slated for Catherine’s urban renewal; Iaroslavl’ Kostroma and Tver’, hence, were redefined.116

* * * *

Iaroslavl’, situated about 250 kilometers northeast of Moscow, was well-positioned to accommodate both the northern and Volga trade. It served uniquely for transshipment and as a commercial center for the fairs which it hosted.117 The city also had a land-based economy, one exploiting the northern forests and textile manufactures for both foreign and home markets. That cattle pastures figured prominently in the landscape joining Iaroslavl’, Kostroma, and Kazan’ suggest still another aspect of the regional economy.118

Having originated as a trading post nearly a thousand years ago, Iaroslavl’ stood second only to Moscow as Russia’s preeminent urban center until the founding of St. Petersburg. The lucrative English and Dutch trade through Arkhangel’sk had brought the city prosperity and stimulated a cultural renaissance evident even today in its comely churches, monasteries, and very own school of icon painting.119 Affluent Iaroslavl’ merchants indulged themselves as patrons of cosmopolitan artists who emulated Western architectural motifs—all before the inroads made by classicism.

This Volga city’s edifices did not, however, mesmerize everyone. After debarking from her cruise in 1767, the Empress Catherine pronounced Iaroslavl’ “beautiful in location but abominable in building.”120 She reiterated this by calling for a new plan to counter the city’s disorder and prevailing woodenness.

Old Iaroslavl’, which backed onto the Volga at its confluence with the river Kotorosl’, was essentially of two parts—the Log City, (Rublennyi Gorod), consisting of the kremlin and cathedral center and Suburb, and the Earthen City (Zemlianoi Gorod).121 Even before Catherine’s reconfiguration of Iaroslavl’ the Rublennyi Gorod received less attention than the Zemlianoi Gorod. The latter, its ramparts anchored by the Spasskii Monastery at the Kostorosl’, invited traffic from Uglich.

One is hard put to ascribe any particular style to modern day Iaroslavl’. It is at once medieval, Muscovite, and classical; even its classicism ran the gamut from that of the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries. A fire in 1768, following Catherine’s visitation, proved an impetus to planning which she had initiated by destroying wooden structures in both the kremlin center and Suburb. The next year she charged the St. Petersburg and Moscow Building Commission to redesign the city.

In 1769 chief architect Aleksei Kvasov proposed the usual division of the city into a center for government and public buildings and the outskirts for housing and the kind of dirty industry and commerce deemed inappropriate nearer in. Like Arkhangel’sk and Vologda, Iaroslavl’s role in internal commerce required its having a sizable storage facility. Two and three story-buildings in the city center were designated for masonry construction; single-story structures, both masonry and wood, were relegated to the outskirts. The rationale for the plan bespoke the usual litany—fire-proofing, sanitation, and aesthetic. No matter, it evoked opposition and was abrogated at the request of the vicegerent, A. P. Mel’gunov. The reason for this rejection is not clear; the Iaroslavl’ plan was hardly atypical. Its lack of distinctiveness may have been the problem, for Kvasov had failed to incorporate those monuments which became centerpieces of the classical city.

Nearly a decade later, in 1777 Iaroslavl’, indicative of its economic and demographic growth was designated a super vicegerency, or governorate; the first holding that office being Mel’gunov.122 Having played a decisive role in disposing of Kvasov’s plan, he immediately pressed for a new one. This plan, possibly of Ivan Starov’s authorship, was completed and confirmed by Catherine the following year.

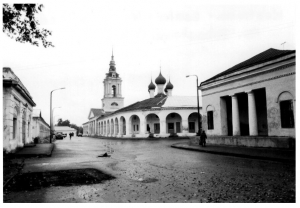

More sophisticated than its predecessors, Starov’s embodied landmarks: encompassing the area between the Volga and the Earthen City boundary, the future classical city took the shape of a trapezoid. Its streets fanned from a central plaza, the Il’inskaia, by the late 1780s Iaroslavl’s hub. Its most important monument was the mid-seventeenth-century Temple of Elijah the Prophet (Khram Il’i Proroka, 1647–50). Before the century’s end two massive administrative edifices joined the church which was positioned at the intersection of the proposed prime axes. One of these paralleled the Volga between the Semenovskie Gates and the Assumption (Uspenskii) Cathedral in the kremlin; two others, pitched to form a trident, stretched from the Elijah Church to the Uglichskie and Vlas’evskie (Znamenskaia Tower) Gates. These two radials—the Rhodestvenskaia and Uglichskaia—were projected to terminate in the plazas at their intersection with Volga-aligned streets. During Alexander I’s reign the first permanent Kotorsl bridge was erected and the Volga embankment stabilized thereby allowing for the construction of a decorative pavilion and promenade (see below) classical landmarks also of Alexander ’s time.

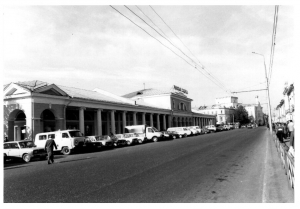

However impressive this building program in Catherinian Iaroslavl’, the making a classical city’, indeed, was Alexandrian. Boulevards replaced the wooden Earthen City ramparts and moats; the bridge across the Medveditskii Ravine was pulled down and the chasm itself partially filled. As noted, stunning stone embankments, walkways, and tasteful edifices transformed the Volga river front! A gostinyi dvor (noted below), contemplated as early as the late 1770s for the site of the old Earthen City wall, was finally realized under Alexander.

Alexandrian Iaroslavl’ has been identified especially with the works of the classicist Petr Yakovlevich Pan’kov (1770–1842).123 This gifted draftsman, who served as provincial architect from 1823–42, was responsible for the mansion ensemble of the governor (1819–20), the city theater (1820), and the Mytnyi Market (1820–23). In the Il’inskaia he built a massive eight–columned Corinthian structure for an expansive bureaucracy before modifying other state buildings there. Pan’kov’s talent for the classical/monumental was further evidenced by a six-columned portico/pedimented theater and the Demidov Lyceum fronted by a towering twelve-columned Corinthian portico without pediment (1825). His Goriainov House, later successively, the Pedagogical Institute and Kommunal’nyi Bank, was also highlighted by powerful Corinthian verandas.

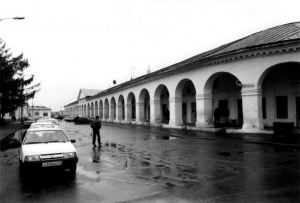

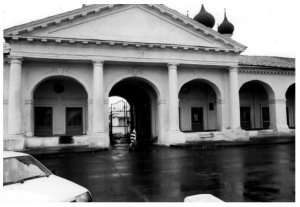

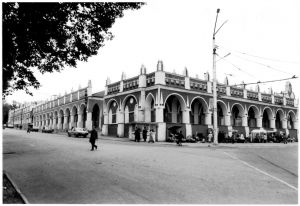

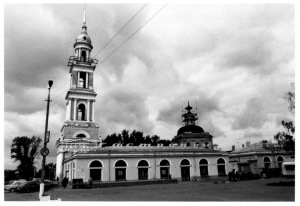

Iaroslavl’s long-awaited gostinyi dvor, another Pan’kov creation, was erected (1814–18) on the site of razed Earthen City walls and centered on the Elijah Church. It was his most distinctive work and among the best of its kind in Russia. Shaped as a trapezoid with Ionic accouterments, it was separated into nearly equal parts by a semicircular entrance. This foyer centerpiece featured a dome and Ionic portico while an Ionic colonnade enveloped the entire building. Taken together these works validated Pan’kov as a master builder of public edifices. Their severity—devoid of rococo embellishment—placed it squarely in the mode of the new classicism.124

* * * *

Kostroma, which dated to the mid-twelfth century, took shape on the north bank of the Volga at its confluence with the Kostroma River.125 Despite the city’s proximity to bustling Iaroslavl’, it was never a notable player in the Arkhangel’sk trade. Rather it faced in an opposite direction, the lower Volga, where its enterprising merchants bartered for silk, engaged in the modest central Russian salt industry, and exploited the sizable timber resources in their midst. The surrounding grasslands, extending all the way to Kazan’, served also as excellent pasture.126

Medieval Kostroma with kremlin and churches possessed a coherence uncommon for historic urban sites: the Monastery of St. Ipaty, at the juncture of the two rivers, was a fixture in the local landscape, both medieval and classical. By Catherine’s time no provincial city in Russia garnered so great an architectural elegance as did Kostroma.127

A signal event in the city’s history which made this possible was the great fire of 1773, which swept away most of the wooden kremlin. This disaster, coupled with Kostroma’s economic expansion, hastened the city’s inclusion in the Catherine’s planning/building repertory. The city’s initial plan (1773), proved inadequate in that cluttered housing continued to impede the straightening of streets. Even a variant plan completed two years later did not immediately improve matters: although it had been decided early on that the city center would be a point of convergence for aligned radial thoroughfares, a 1775 version underwent successive modifications in 1778 and 1779; another correction by the Commission for the Building of St. Petersburg and Moscow settled the plan’s approval on 6 March 1781. Entered into the Code of Law of the Russian Empire, the plan, nevertheless, was even revised several times prior to 1784.

This final draft retained the kremlin and its rebuilt (1775–78) Dormition Cathedral. Further, it preserved the concept of earlier plans, the city’s opening to the Volga and the web of axes which fanned from the central plaza just up from the river.128 The Pavlovskaia, new Kostroma’s main axis, ran perpendicular to the Volga in a northeast/southwest direction with the Mshanskaia, Eleninskaia, among others on one side and the Mar’inskaia, Blagoveshchenskaia, Rusina/Kineshemskaia, and Debrinskaia on the other. In this exquisite composition, which resembled spokes of a wheel, the Mshanskaia and Debrinskaia ran parallel to the embankment.

While classical Kostroma’s hallmark was this pentahedral plaza and web of converging arterial thoroughfares, the architects of the 1784 plan had other matters to attend. They became especially preoccupied with the form and composition of the plazas and blocks (kvartaly)—and how and where to locate public buildings and trading rows or arcades. Between 1776–92 work on cathedrals proceeded under architect Stepan A. Vorotilov (1741–92), who restored the burned-out Assumption (Uspenskii) and completed the Epiphany (Bogoiavlenskii) and bell tower ensemble. In 1792 he added the Red Arcade bell tower next to the Church of the Transfiguration, a five-cupola church of an earlier vintage. The Red and Large Flour Arcades (1789–93) were the most important of this mélange of white columnar market halls which skirted Kostroma’s central plaza. As the Red Arcade/quadrangle had organized the Kostroma center in the 1790s, the elegant Trifle Arcade similarly approximated this role a generation later. Although Vorotilov had laid out the central plazas and initiated work on the embankments and the Pavlovskaia and Eleninskaia radials, Kostroma’s grand scheme took shape gradually. Meanwhile, filling in old ditches and moats proceeded.

Besides Vorotilov, the architectural cadres responsible for forging classical Kostroma, included Karl Kler, Nikolai Metlin, and Petr Fursov. Kler joined Vorotilov in work on the Large Flour Arcade quadrangle. Metlin, an architect’s son who had worked in Moscow, was responsible in 1799–1800 for a public meeting house (Obshchestvennyi Sobranye), the Bread or Kvass Shops, a state office building, and the Butter Stalls in 1808. Even the St. Petersburg architect, Vasilii Stasov had a hand in designing the Tobacco, Fish, Butter, and other trade rows adjacent to the central square.129

The most famous of Kostroma’s architects was Petr Ivanovich Fursov, whose creations dominated this plaza.130 Fursov, who worked in the city for nearly three decades, designed the Trifle Trade Quadrangle which in some ways matched Vorotilov’s earlier Red Arcade. Beyond the trade rows his Hauptwacht, or guardhouse (1823–25), is a Doric gem of brick. Reminiscent of Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s Neue Wache on the Unter den Linden in Berlin, it lay wedged between converging streets in the central plaza.131

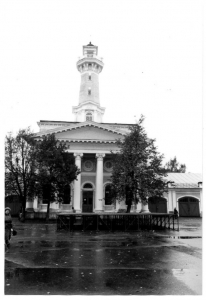

Fursov’s Fire Tower, Kostroma’s signature piece, was built in 1823–26, also in the square.132 The dominant features of this building were its imposing tower and what resembled an Ionic temple at its base. Called by historian Brumfield “perhaps the greatest work of the city’s neoclassical renaissance,” the building combined elegance with practicality: its central block provided for administrative staff and firefighter housing, while single-story arcaded structures on each side accommodated stables and carriages.133 Above all, the voluted and rusticated watchtower allowed for early fire warning. Because of this worry about fire, timber housing, which crowded the avenues leading into the center, was regularly replaced by elegant two-story homes as on the Eleninskaia, Rusina, Pavlovskaia, and Upper (Verkhniana) Avenues, and along the embankments.134

The Built Environment of Kostroma Center

More than any other classical city in provincial Russia, Kostroma has preserved the magnificence of the architectural ensemble at its center. Completed in the mid-nineteenth century, it constituted a masterful integration of urban design and architecture. In its final version Kostroma achieved symmetry, an articulated center, straightened and widened streets, spacious and adorned plazas, uniform facade design, a set ratio of street width to building heights, and an enforced red line (krasnii linii), which established the positioning of street facades. All these factors made Kostroma a model of Russian urban classicism.

* * * *

Tver’ and Torzhok, separated by only 60 kilometers, suggests a coupling like that of medieval Novgorod and Pskov. Such a comparison is misleading: Tver’ was not an important Volga trader; medieval and early modern Torzhok, on the other hand, looked to Novgorod and St. Petersburg for commerce. The coupling occurred only during Catherine II’s reign when each acquired a neoclassical look and became, not surprisingly, imperial favorites.

Tver’ vied during its early history—the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries—f or regional hegemony with Vladimir, Rostov, and Moscow. By the fifteenth, however, the principality had become little more than an administrative appendage of Moscow. Instead of river trade which had energized Iaroslavl’ and Kostroma, Tver’ developed a more diverse economy, which included livestock, vegetables, flax, hemp, honey, bees wax, and even crafts.

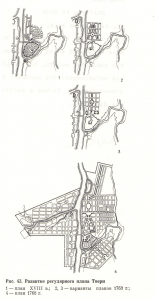

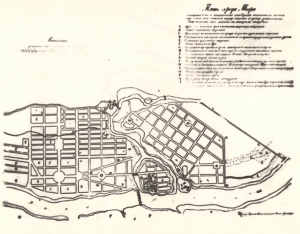

Situated on the Volga at the juncture of the Tvertsa and Tmaka Rivers, eighteenth century Tver’ occupied mainly the right or south bank. The Tvertsa flows into the Volga from the north through a district beyond the Volga, or Zavolzhie.. The Tmaka, which partially enveloped the old kremlin, joins the Volga from the south (west of its confluence with the Tversa). In Catherine’s day the thirteenth-century Otroch’ Monastery was the principal occupant of the sparsely-settled strip between the Tvertsa and the Tmaka.

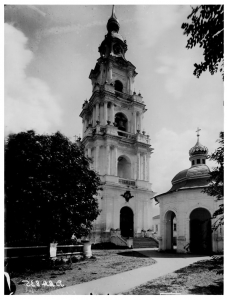

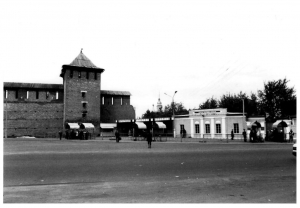

Because the restoration of Tver’ was the first provincial application of lessons learned from Peter the Great’s founding of St. Petersburg, classical Tver became an urban milestone for Russia.135 The 1763 fire consumed the old city in a day, incinerating nearly every structure within the Gorodskii Posad and outside the kremlin walls.136 Restoration of the city fell to the St. Petersburg/ Moscow Commission for Masonry Building, established by the Senate the year earlier to alter Moscow, and headed by General Ivan I. Betskii.137 Acting for the Commission Betskii prescribed reguliarnost’ with St. Petersburg in mind: wide, linear thoroughfares and expansive squares for public buildings. Similarly, he enforced the law for housing modes.138 The Tver’ operation was important because it enlarged the scope of the Commission’s work and most likely its tenure; henceforth, it became Catherine’s paramount planning and building apparatus for the entirety of her reign.

Within days after the fire, architect Petr Nikitin was dispatched to Tver’ to assess the damage and begin work on a new plan for the stricken city.139 Nikitin, who at the time headed the Ukhtomskii Architectural School in Moscow, was joined by architect Aleksei Kvasov of the St. Petersburg/ Moscow Commission.140 Because desolated Tver’ required an immediate and total overhaul, the architects and their assistants were a diverse lot, not merely Commission members. Nikitin brought with him members of his academic staff—Ivan Parfentiev, Prince N. Meshcherskii, and P. or N. Bartenev. He was joined also by General V. V. Fermor and two other Ukhtomskii School pupils, Petr Obukhov and Matvei Fedorovich Kazakov.141 Although not often associated with Tver’s restoration, Fermor as director of construction did exercise considerable influence on the outcome. Kazakov, the youngest and least experienced, was one of Ukhtomskii’s prize students; it was he who emerged a star in Tver’s rebuilding, eventually winning acclaim as Russia’s premier architect of classicism.

The rebuilding of Tver’ was significant: despite her disdain for most provincial cities, Catherine took an extraordinary liking to this one. Fortunately, she had a very responsible governor, Jacob Sievers, in charge.142 Even so, the rebuilding was at times contentious—a classic instance of imperial dictates in conflict with the wishes of the city’s populace. These differences had mainly to do with housing. Catherine confirmed and Betskii insisted on masonry houses with continuous facades, as designed by Nikitin and Kvasov. However essential these substantial houses were to the “whole city” concept, they were opposed by property owners because of cost and encroachment on their rights. Fermor, sensitive to citizens’ plight, was caught in the middle. He evidently questioned other aspects of the Nikitin/Kvasov plans thereby securing modifications.143 When Catherine visited Tver’ in early May, 1767, only houses along the Grand Prospective and the Volga Quay had continuous facades.144 This tension in Tver’ suggests that urban planning under Catherine and Alexander was not always so harmonious as the sanitized accounts by Soviet and Russian historians contend.

Nikitin’s plan concentrated initially on the city’s right bank. After its submission to the Commission, the prospectus was forwarded to Catherine II who approved it in 1767. Within the decade the areas beyond the Volga (Zavolzhskaia) and Tvertsa (Zatveretskaia), which burned in 1773, and that beyond the Tmaka were incorporated into the Tver’ plan as well. The earliest and most important of these plans, that for the right bank, called for rebuilding the kremlin and certain structures within its walls. In any case, the Salvation/Transfiguration Cathedral (Spaso-Preobrazhenskii Sobor) of 1689–96, governor’s residence and office, the garrison barracks, hospital, and post office appeared anew. The architects made the kremlin the locus for radial streets.

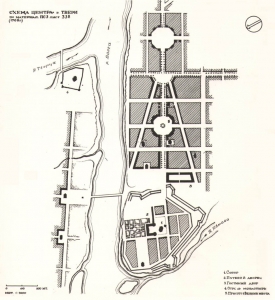

Nikitin’s Tver’ was essentially fan-shaped: the middle radial, the Moscow—St. Petersburg road, was the designated east-west axis and middle prong of a trident. Called variously Voznesenskaia, Millionaia, Sovetskaia, and then Voznesenskaia again, it was and is the city’s main thoroughfare, forming elegant portals into Tver’ from both St. Petersburg and Moscow. Wide and tastefully planted with greenery, they set the tone for a classical Tver’.

Three separate open spaces were conceived for the Voznesenskaia axis: the Circular Plaza, initially inconsequential, was planned with commerce in mind; the Semicircular Place, from which the trident of axial streets radiated; and the octagonal Fontannaia (called variously the Catherine and Octagonal) Plaza, was projected for ministry offices.145 This three-pronged layout, while suggestive of the ray of streets converging on the Admiralty arch in St. Petersburg, actually reversed that pattern, for the Tver’ radials diverged to separate sections of the kremlin wall. The Voznesenskaia axis stretched from the Fontannaia to mid-eighteenth century Sobor belfry; the left ray settled on the corner tower while the one on the right came to rest at the Volga crossing. This prospect confirmed Nikitin’s considerable regard for the city’s historic center: a refurbished Red Square to the right of the kremlin entrance opened a view to that part of the city beyond the Volga with its web of streets and single-story houses; conversely from the Petersburg road in Zavolzhie, the kremlin hill was neatly profiled. Beyond the Fontannaia, along the river, a stone embankment with controversial model houses served as backdrop.146

The Nikitin cadre developed plans for government office buildings, model commercial establishments, and elegant residences in the city’s center. In fact, constructing downtown Tver’ proved a long term enterprise. Continuing until the middle of the next century, it remained generally in accord with the thinking of the 1760s planners. Nikitin even pondered erecting commercial buildings on the city center perimeter quite apart from the shopping arcade, which was completed in 1768. Merchant homes, often above their first-floor shops, prevailed in downtown Tver’. Those on the Voznesenskaia/Millionnaia, especially, radiated genteel classical decor.147

The most distinctive architectural creation in restored Tver’ was the Putevoi Palace, intended for the empress when in residence. This reconstructed edifice, a palace that once had belonged to the bishop, was the work of young Matvei Kazakov between 1763–75. Situated within the kremlin, it was surrounded by gardens overlooking the Volga. The palace floor plan was that of an inverted “U”, a three story main building with single story open galleries reaching forward to pavilions on each side of the entrance. The cupolas capping the pavilions gave the building its flair.148 This early structure was altered several times, initially by Alexander I’s celebrated architect Rossi, who converted the Putevoi (1809) into a palace of late classicism.149 Like Kazakov a generation earlier, Rossi parlayed his work in Tver’ to launch an auspicious career designing spacious St. Petersburg ensembles.150

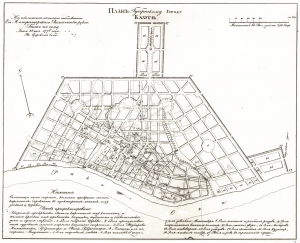

As provincial heir to elegant St. Petersburg, reconstructed Tver’ proved a visual feast. Deriving grandeur from its axial thoroughfares and architecture and perched at the confluence of three rivers, the city became a prototype for classical planning in provincial Russia.151 Catherine, enchanted, confided to Melchior Grimm: “After Petersburg, Tver’ is the most beautiful city in the Empire.”152 When a fire swept Kazan’ in 1766, she ordered her Commission to rebuild the city “according to the plan of Tver’.”153 That another Ukhtomskii student, Vasilii Kaftdyrev undertook that task is not surprising.

Nearby Torzhok famously won Catherine’s approval as well.154 Like Novgorod and Tver’ that city’s fate was one of annexation by Muscovy late in the fifteenth century. The founding of St. Petersburg initially proved beneficial to Torzhok, for the city, according to William Brumfield, received “a new market square and arcaded market buildings” as well as numerous homes of the affluent, all, of course, in the classical mode.155 In 1815–22, the cathedral, the Transfiguration of the Savior, was rebuilt according to a plan by Rossi, and the ancient Monastery of Saints. Boris and Gleb in accord with one by architect Nikolai Lvov. Brumfield has called this monastery “one of the greatest monuments of Russian neoclassicism.”156 Although a lesser entity than Tver’, Torzhok, nonetheless, did prove a superb example of Catherinian classicism.157

* * * *

While towns south of Moscow frequently evolved from fortresses, Kaluga, like Iaroslavl’ and Kostroma, was possessed of a commercial narrative.158 Arcadius Kahan describes a mega-region which took shape early in the seventeenth century—one stretching from Kaluga, Riazan, and Tula through the black soil region to Kiev.159 In it Kaluga became the dominant regional market for fish and meat and for that reason a center of the salt trade as well as for hemp and wax as well as a transshipment point for boats and carts destined for either Moscow or the steppe.

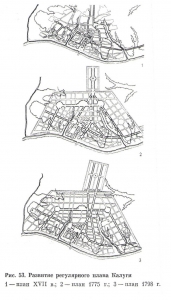

Whereas catastrophes not infrequently caused both the undoing as well as remaking of cities, the determinant of affluent Kaluga’s fate was less spectacular: its transformation lay in its new status, its designation as namestnichestvo, which occurred in August, 1764. Thereafter, the initiative of the city’s first namestnik, M. N. Krechetnikov, led to the 1778 plan drafted by Petr Nikitin.

Nikitin’s classical Kaluga approximated a trapezoid with a kreml’ and strategic crossroad in its midst.160 Originally a wooden stockade, the kremlin quite simply had spawned the city. Wedged between the Berezuika and Gorodenka tributaries, it occupied high ground above the Oka River while at the same time turning inward toward the city. Here it reached a level with the roads approaching it from both Moscow in the north and Tula in the southeast. That point where the two roads intersected was the second pivotal location of a planned Kaluga. Historian T.M. Sytina called the old Moscow Road the compositional axis of the entire planning structure. Both landmarks, the. kremlin and the crossroads, facilitated Kaluga’s having a regulated or geometric center separated from its suburb by axial thoroughfares.161 Because the road juncture had been the site of the city market, a showy red brick gostinyi dvor was built there in the 1780s–90s.

While classical Kaluga’s midsection followed along the Moscow Road, the city stretched from Zhirovskii Brook on the city’s eastern edge (north of the Tula Road), to the old Smolensk Road in the southwest. Regulated plazas on the site of the old Iamskaia Sloboda improved appearances at both ends of the Tula-Moscow Road. The circular Sennaia in the northwest section of the city, projected in the 1778 plan but not realized until the next century, radiated in all directions. Although inexact as a radial-centric model, it did have positive aspects. Diagonals on the left and right of north-south axes formed fans or tridents, thus creating a grid of squares and parallelograms. Aside from its kremlin hub and Moscow-Tula axis, this multiplicity of radials, fans, circles, and grids became the most dazzling feature of Nikitin’s classical Kaluga.

Just as commerce had spurred the city’s growth along the Moscow Road, its administrative center evolved on kremlin hill between the Oka and Berekzuiskii Ravine. The Nikitin plan projected a plaza comprising administrative buildings and the cathedral. On the south side of this square, on the Oka bluffs, burgeoned residences of the governor and vice-governor162 By the late eighteenth century the Gorodenka River had reverted to a dry ravine.

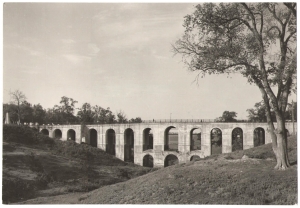

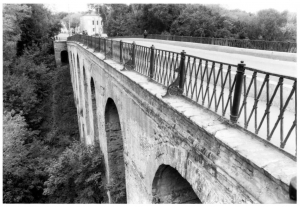

A massive stone portal flanked by twin Tuscan columns and obelisks was erected in 1775 to welcome the visiting empress. Most of this Moscow Gate, the creation by an unknown architect, has since disappeared; however, a stone bridge by Nikitin is still very much part of the Kaluga landscape. Spanning Berezuiskii Ravine and completed in 1780, it is a powerful structure, suggestive of a Roman aqueduct with two tiers of arches at its highest point.163

New Kaluga’s first official edifice was the governor-general’s summer residence, a frame structure fixed above the Iachenki River just outside the city. Although it did not survive, it is known from a drawing by architect Ivan Denisovich Iasnygin (1745–1824), who produced an album of city and regional facades in 1796–97. Iasnygin proved a key player in the making of classical Kaluga. Having worked under Vasilii Bazhenov and Matvei Kazakov on the Moscow Kremlin before his arrival in Kaluga, he served as its provincial architect from 1785 until retiring in 1822. Although Nikitin had initial responsibility for the city’s administrative complex, it was the younger man, who designed the separate buildings and saw each to completion in 1787. His first known work in Kaluga was a salt store, a single story building on the Oka and completed in 1787. His two administrative buildings and seminary, which formed a quadrangle embracing the cathedral, were massive and not unlike kindred types opposite the Elija Church in Iaroslavl’.164

The classical Troitskii Cathedral was yet another Iasnygin creation. Conceived in the form of a Greek cross, this temple-like edifice took years (1784–96) to build. Eventually the building was capped with a dome and joined on one side to a looming bell tower. Colonaded facades and porticoes with pediments bedecked both buildings, allowing the pair to exude a quiet elegance in a garden setting.

While the Troitskii Sobor was under construction, Iasnygin worked elsewhere in Kaluga. In 1806 he designed a residence for the governor but had to modify the draft to meet standards determined in St. Petersburg. Fortunately, that model was a creation by Adrian D. Zakharov, architect of the Admiralty. Although this exercise of centralized control delayed its completion for a decade, Iasnygin successfully completed the stately house of the Vice Governor Zagriazhskii during these same years.165

The Kaluga business center, which lay only a short distance from this sylvan hilltop setting, also challenged the city’s architects. A massive arch in the northern segment of the administrative building flanking the cathedral opened into the world of commercial Kaluga. At the juncture of Moscow-Tula road rose the architectural oddity noted above, the pseudo-Gothic gostiny dvor or commercial arcade of brick and white stone, probably initiated by Nikitin. As with Troitskii Cathedral, its construction seemed never ending. About 1811 Iasnygin was charged to draft a new design. Although he never completed it, he did make substantial changes. Stretching nearly the length of the square and colorfully displaying the arches and pinnacles of its arcade, this edifice of shops left no doubt that commerce had a singular place in classical Kaluga.

Despite Kaluga’s impressive official and commercial buildings, its public edifices and mansions especially advertised the city’s wealth and sophistication in planning and building. Churches, almshouses, orphanages, and hospitals—endowed by the affluent in remarkable numbers—became hallmarks of this classical city. One such building was the Khliustinskaia Hospital, designed by the serf architect I. Ia. Kashirin, who had worked under Iasnygin.166